Chapter 1 - Childhood and Early Life

I was born at Pound House in the hamlet of Ledstone, a farming community near Kingsbridge, South Devon, on 23rd September 1900. We were a large family, though not unusually so for those days. I was the 10th child of a family that eventually comprised 8 girls and 6 boys born to William and Emma Stone.

I was born at Pound House in the hamlet of Ledstone, a farming community near Kingsbridge, South Devon, on 23rd September 1900. We were a large family, though not unusually so for those days. I was the 10th child of a family that eventually comprised 8 girls and 6 boys born to William and Emma Stone.

The family had a great naval tradition. My father had 3 brothers who had "done their full time" during the nineteenth century - one had been a Master at Arms. My mother also had a brother who had done his full time. Three of my brothers and I all joined the Royal Navy. My father never saw military service himself as he had fallen off a horse when he was younger and had broken his arm. The arm had not set correctly and was always a bit crooked. I remember that he also had a pit in his forehead which had been caused during the same accident - as he had fallen from the horse he had hit his head on a plough shear.

My father worked on farms all around the South Hams area of South Devon. He was skilled and could turn his hand to most jobs that cropped up on a farm. He could operate many agricultural machines like the steam driven threshing machine or steamroller. He also slaughtered and butchered pigs. Most people in those days kept a pig or two. My father charged a shilling, five pence in today's money, for killing and cleaning up the pig and an extra sixpence, two and a half pence in today's money, to return the next morning and cut up the carcass. He was left-handed and the local butcher said that he could tell which pigs father had butchered by the way they had been cut up. As children, we all helped him with his work on occasions. In those days on a local farm there was no stunning of the animals before they were killed which was done by slitting their throats. He would allow us to work on the rear of the animal whilst he dealt with the head. We would sometimes have an informal biology lesson. Father would explain that the pig's insides were in many ways similar to a human's and would show us things like the animal's appendix. I don't know what he would think of the modern idea of using a pig's heart in a human - it's not something I would want myself! Once butchered the meat was salted down. Salt was added to water until a potato would float in it. This gave the correct mixture for the brine in which the meat was preserved. Although all of us boys helped Father when we were young, we all thought that it was a dirty job and none of us followed his trade when we grew up.

My eldest brother, George, broke with the family's naval tradition and joined the Royal Horse Artillery. The last time I ever saw him was about 1908 when he cycled down to South Devon all the way from London. What happened to him after that I never knew, though I gather he died in India. Years later another of my brothers, Jack, who was also in the Royal Navy, was in India and tried to find him, but George had apparently died some time before.

Jack served in the Royal Navy for 22 years, rising to the rank of Petty Officer. I remember that at one time he was on the destroyer H.M.S. Isis and I was on a party from "Hood" that was responsible for refuelling her.

Walter, who was about three or four years older than me, also served his full time in the Navy.

Lawrence, who was 18 months younger than me, followed me into the Navy. In fact he did more than that - he followed me to my first ship, H.M.S. Tiger. Lawrie finished his naval career holding the rank of a Petty Officer, having served about 24 years.

My youngest brother, Cecil, followed George by joining the Army and was in the R.E.M.E. but he was only in the Second World War.

My earliest memories go back to 1903, when I was 3 years old. It was then that I started my schooling, which took place at the village school in Goveton, near Kingsbridge and lasted until I was 13. At the end of what turned out to be my final term I remember the teacher, Miss Collins, saying "I shall not need you again next term Billy," and that was that!

Chapter 2 - Devon Days

Having finished my schooling I needed to find myself a job. My father was able to point me in the direction of a farmer, Mr George Giles, who had mentioned that he needed a boy to help out. I went along to the farm, Sherford Down, at Sherford, a village near Kingsbridge and asked the farmer if he would take me on. "When can you start?" asked the farmer, "Today," I replied. "And what wage do you want?" "Well, my Father said half a crown a week", said I. "Mmm, sounds a lot," came the reply. Of course, it wasn't a lot at all as my father knew the going rate. Eventually terms were agreed.

So it was that, aged 13, I left my family home. The job on the farm, although it was only 2 or 3 miles away, was on a live-in basis. I shared a bedroom with two others, the head horseman Bert Tucker and the second horseman Dick Tucker – cousins. At 5.55am the farmer would ring the bell, from his bedroom, and five minutes later ring it again for us to get up. Some years later Bert, the elder, joined the Royal Marines and was lost along with Lord Kitchener when H.M.S. Hampshire was sunk. I had often done odd jobs on the farm during my boyhood days - helping to clip hedges and jobs like that in the evenings or at the week-end. It earned you a few pence that you could look forward to spending, particularly when the fair visited Kingsbridge.

I had all kinds of jobs on the farm. In those days farms didn't specialise in one form of livestock like they do now. The farm that I worked on kept cattle, pigs, and hens as well as growing fodder crops.

Morning often started with guiding the cattle to the milking shed. Being a local man born and bred, the farmer would only keep South Devon cattle. Of course, back then, all milking was done by hand. I remember the first time I had a go at milking, I happened to choose a cow which had just had her first calf. Like me, she was new to the game of milking and didn't take kindly to it. As soon as I started she kicked violently and over went the bucket. For a while after that I was designated a novice and the farmer made a point of following me around. He always managed to get more milk out of the cow. It was important that all the milk was drawn out of each animal as if this was not done they would dry up sooner. Most days we would each milk 12 to 14 cows and eventually I mastered the technique. I also got the hang of choosing the cows that were less likely to make a fuss about being milked!

The farmer would keep a supply of milk for use by his family and sell some to the villagers. Some was put through a hand-operated separator, which removed the cream from the milk. The cream was used to make butter and the remaining thin milk given to the pigs and cattle. The farmer’s wife would make the butter by hand (sometimes my mother would help) and on market day take it, together with eggs from the hens, to sell at Kingsbridge market.

I cleared the manure from the sheds and the other men cleared the stables. All the manure was put into a large pit behind the stables and later in the year taken by horse and cart and spread over the fields. The farmer grew acres of mangolds, a sort of root vegetable, which were used as fodder for the cattle. When the mangolds were ready to harvest we would pull them up, cut off the tops and store them by a hedge, covered in straw and hedge parings to protect them from the winter frost.

Along with my "official" duties at the farm went my other role of rat catcher. Mr Giles, the farmer, would give me a penny for each rat I caught and I remember that, at one point, I was doing so well that he thought I was bringing the same rat to him twice! "I've paid you for this one before, haven't I Bill?" he would say. After that, just to make sure he was getting his pennyworth he made a point of cutting off the tail of each rat as I claimed my reward so that he knew that a second claim could not be made!

A year after I started work the First World War began. My elder brothers had joined the Royal Navy and soon I was eager to follow suit. I went to Kingsbridge to enquire about entry and passed all the necessary tests. However, when I took the forms home for my father to sign he refused to do so saying that he already had 2 sons in the Navy and that I was too young anyway, so the papers were sent back.

Around the same time, aged about 15, I left the farm and got another job. I started work for a haulage company at Kingsbridge driving a horse and cart delivering flour, amongst other things. In the summer I would water the streets with a horse-drawn water cart to dampen down the dust. (This was before tarmac was used as a surface.)

Later, I was employed as a second ‘hand’ driving a steamroller for the council. We used to work on the local roads laying chippings and rolling them in to make a metalled surface. Later still I moved up to a 12-ton engine. Again, this was steam powered and similar to a traction engine that one might see at fairs these days. Operating such a vehicle was a two-man job. One man would be responsible for driving it which involved keeping the boiler going and dealing with steam pressure and the like. The other man was responsible for steering. We would rotate these jobs so that we kept our hand in at both duties. One of our regular runs was to visit a local copse where trees were being felled. We pulled the wood to the engine using a winch and then we cut it up into planks with a circular saw, driven by the engine. We would take the wood to Kingsbridge station and leave the engine there for the night. I would drive it back to the woods and one of the men would steer it. This was my last local job before I joined the Navy and, as will be seen, had an influence on my duties during my first weeks of service.

Chapter 3 - I Join the Royal Navy

As my 18th Birthday approached, I again started to think about joining the Royal Navy. Two weeks before my birthday, some papers arrived in the post informing me that I should report to Exeter to undergo a medical in preparation for joining the Army. "Not likely," I said, "I'm a Navy man and I'll be on the next train to Plymouth!"

As I have mentioned, my work at that time had been driving a 12 ton engine, so I gave the firm a week's notice and made my way to Plymouth to ensure that my future career would be a naval rather than a military one. I succeeded in signing up but, when I got home and told my brother that I had joined as a seaman, he replied, "What did you want to go and do that for? You are supposed to be in the Engine Room Department." Following his advice, when I went back to Plymouth I swapped over and became a stoker.

Whilst I was undergoing my initial training at Plymouth the country was struck by a 'flu epidemic. Thousands died during the outbreak and I was quite ill myself for a while. We were all billeted in tents at the time - about 4 to 6 men in each tent at St. Budeaux, near Devonport Barracks, Plymouth. I remember that I had collapsed over my dinner as I was eating it and when I woke up I was in the Naval Barracks! We were put into the gymnasium, which had been converted into a makeshift sick bay and was full with patients. I was there for about 10 days. Part of our "treatment" involved being fumigated. We were marched into a room about 50 at a time. The room was then filled with a mixture of steam and disinfectant fluid. Our clothes were given a similar treatment and we were advised to regularly gargle with a solution of Condy's Crystals. Once recovered, we were sent home for about 10 days' leave.

Eventually, I returned to good health and finished off my training. I then received my first draft. I was to proceed to Rosyth by rail to join my first ship - the Battle Cruiser H.M.S. Tiger. "Tiger" was a famous ship - one of Admiral Beatty's "Splendid Cats" of the 1st Battle Cruiser Squadron, which had seen action during the Great War at Dogger Bank and Jutland.

However, another duty awaited me before I joined ship. There was a rail strike during 1919 and my papers showed me as a "driver". On the basis of this intelligence I was sent to Newport in South Wales to help out with essential work on the railway during the strike.

When I got there, I was able to clear up the fact that my driving had been in traction engines rather than in railway engines. However, when they found out that I was joining the Royal Navy as a stoker, they decided that I should practice my new trade by working as a fireman or prospective engine driver for two to three weeks. In fact, I had occasionally had a go in a steam engine in the sidings of South Devon during my youth so I did have an idea of how to drive a train. However, during the strike, my own engine driving was restricted to shunting around the station and goods yards. One engine I drove was called “Baden Powell,” but some of the Engine Room Artificers from the Navy got to do longer runs on the main line.

In my first few days there I slept in the sheds but after a while I managed to find some temporary accommodation in Newport.

Of course, we sailors were not very popular with the locals and the strikers. We were called "black scabs" to begin with. Our reply to that was that being in the Navy we went where we were pushed! Eventually most of them accepted that we were not volunteer strikebreakers.

Chapter 4 - My First Ships: H.M.S. Tiger

When the rail strike finished I took a train north to join "Tiger" at Rosyth. On that journey, I remember sleeping in the luggage racks in the compartments on the way up.

The first thing that I had to get used to on joining "Tiger" was the routine of shipboard life. We stokers slept in hammocks on the mess deck and each morning the Chief Stoker, in my case a man by the name of Darby Kelly, would come around to make sure that everyone got up on time.

On the first morning that I was aboard he came around at quarter past five and I somehow managed to get up. The next morning it was about half past five when he came around shouting, "Out of those bloody hammocks!" Everybody seemed to be out of their hammocks except me. He came up to me and shouted, "What the bloody hell's wrong with you? Out of that bloody hammock at once and run down the passage singing 'Should old acquaintance be forgot'!" I fell out of my hammock - much to the amusement of all my messmates who all knew 'Chief' of old. They tell me "Chief Stokers never die…" I suppose they had to be pretty hard as there were about 400 stokers on the "Tiger."

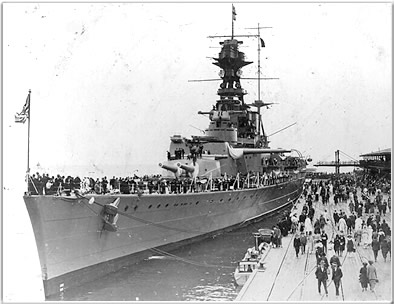

H.M.S. Tiger

Having managed to get up, the day's routine would start with breakfast before setting to work. Then, at 11.30, came the call "Cooks to the Galley!" Two men from each mess would be assigned as "cooks of the day" and it was their job to prepare the food that day for all the men in their mess. This might involve jobs such as peeling potatoes, preparing vegetables and cutting up the half a pound per man meat allowance to make a pie. Having put on the crust you would take the pie and other food back to the galley to be cooked.

Shortly after I joined H.M.S. Tiger, we were at Scapa Flow where the German High Sea Fleet had been interred at the end of the War under the terms of the Armistice to await a decision on their ultimate fate. It was there on 21st June 1919 that Rear Admiral Reuter gave the secret signal for the entire fleet to be scuttled. During my early days in "Tiger" you could still see the funnels and masts of some of the ships, which had gone down in shallow water.

To my mind the scuttling of these ships was probably the best thing that could have happened in the circumstances. I think that, had the Germans not taken the initiative, there would have been a lot of political arguments between Great Britain, the United States and France about how the High Seas Fleet was to be divided up between the victors of the Great War.

Whilst in "Tiger" I worked as a stoker in the Engine Room department. There were 39 Babcock and Wilcox boilers. I well remember the duty of coaling ship when all hands including the officers would join in as we took on thousands of tons of coal, and the Marine Band would play. Following the scuttling of the High Sea Fleet, "Tiger" spent a while in the docks at Rosyth having some of her coalbunkers converted to oil fuel. At this time she was 50% coal, 50% oil and would normally start a trip on coal before switching to oil. The coal burning boilers would get covered in clinker, which we stokers had to clear out. Having let the fire in the boiler to be cleaned burn down, we would then pull out the clinker and ash. The ship had ejectors for ash, which was mixed with salt water before being blown out of the sides of the ship. To get the boiler running again following the cleaning process, we had to break the lumps of coal down into knobbly chunks and build up a layer on the fire bars prior to lighting the boiler. Boilers were usually de-ashed every 24 hours.

Our next cruise took us to Gibraltar and around some of the Spanish ports. I remember visiting Vigo and buying “4711 Eau-de-Cologne” for Mother, and a Jacobs pipe for Father.

In 1920 came my first contact with the "Hood." "Tiger" accompanied "Hood" on her first overseas cruise, which was around Denmark, Norway and Sweden during May and June of that year. We anchored at Nynashamn and a group of us sailors went ashore and caught the train to Stockholm. We should have caught the midnight train back but saw it leaving the station! We eventually reported back to ship “12 hours adrift” and were put in the Commander’s Report. My excuse was that I couldn’t find the station to which the Commander replied, “Next time don’t leave the station!” We were stopped four days’ pay.

In 1921, we went on the usual spring cruise to the Mediterranean. On this occasion, we were not allowed to be in contact with the men from the ships of the Mediterranean Fleet as they were suffering from another epidemic of 'flu.

There were, however, still regattas and races between the visiting ships of the Battle Cruiser Squadron. In these "Tiger" did not fare so well. The reason for this was that, when "Hood" had first commissioned, many of the men had been taken from the "Tiger's" sister ship "Lion." These men were the finest oarsmen in the fleet and "Tiger's" crew stood little chance when pitched against them in the cutter races. I used to take part in the cutter races myself. A cutter was a boat, which was "pulled" (i.e. rowed with oars) by 8 men.

I also remember another incident whilst we were at Gibraltar. I was out for a run trying to keep myself fit when I passed by the brothel. The girl on the door spotted me as a sailor and greeted me with shouts of "Over here, Jack," but I kept running!

In these early days we would regularly call in at Malta, which I remember as being a great place to be. There could be a dozen big ships in the Grand harbour in those days - "Tiger," "Ramillies" and all the others. The streets would be packed with sailors. I tended not to go ashore myself until later on in the month - just before payday was a good time. That way the place would be a bit less busy as a lot of the sailors would have run out of money. Every door seemed to be either a pub or a café.

The whole Maltese economy seemed to be based on the British Fleet in those days. The locals would come on board to clear away after meals and do the washing up. They took away any left over food and sold it in the towns and villages on a "penny a dip" basis. That used to make me laugh as the larger your hand the more you got for your penny. We would often give them a loaf to take away as well. There were also locals running ferries to and from the jetties. Others came on board to take away the washing, which they would return the next day. You could even have someone come on board and measure you for a suit.

After I had been in "Tiger" a while I started to look around for a spare time occupation aboard ship from which I might be able to earn a little extra cash to supplement my Naval pay. In due course I decided that I would have a go at tobacco rolling. Back then; tobacco arrived on board in the form of loose leaves. Of course, most men smoked in those days and it was common for someone to buy a pound of tobacco at a time to last them the month. A pound of tobacco cost about 18d back then. Having bought the whole loose leaves, the men would bring them to me to prepare. The first stage of the preparation process involved cutting out the black stems of the leaves - from which snuff could be made. Having done that, you then had to damp the leaves and roll them tightly into an elliptical shape, which was fat in the middle and tapered to two pointed ends. Canvas was wrapped around followed by spun yarn - wound tightly all around. The leaves could be stored in this form and remain fresh. The men would cut tobacco off to use for roll-ups, as they needed.

I left "Tiger" in 1921 and returned, as one always did, to barracks at my homeport of Devonport to await my next draft. Whilst I was in the barracks I met an old Chief who was leaving the Navy on a pension. He had been the barber in his ship and wanted to sell his clippers now that he was leaving. I thought that this might be a good way to earn a little more money whilst aboard my next ship so I said I would buy them from him. I paid £1 for which I got a full set of clippers: No.1, No.2, No. 3, comb and scissors. I didn't realise at the time that not only would this purchase earn me extra cash to supplement my Navy pay, but it would be the start of a whole new career for me - one that would even outlast my days in the Royal Navy.

Eventually, came news of my draft to "Hood." Usually, when one was drafted a number of men stationed in barracks went together, but my draft to "Hood" was unusual in so much as I was the only one who joined her at that time.

Chapter 5 - Around the World in H.M.S. Hood

In January 1923 I joined "Hood" at my homeport of Devonport and, once aboard her, I decided that I would lose no time in putting my barbering skills to the test. Although I had not received any training at all in barbering, my father had cut all the boys' hair at home so I had picked up a few tips from him. I had also watched barbers cutting hair in a local shop. Although "Hood" did not have an official barber as such, she did have a cabin fitted out as a barber's shop. This had room for two barbers. Unfortunately, when I joined both positions were already taken. Rather than wait for one of the positions to become vacant, which might not happen for some time, I decided to set up on ‘the flats’ (the small open areas between the decks.)

Not long afterwards, some of the crew had made it known that they were not happy with the barber who currently occupied the barber's shop. One of the Commanders asked the Master on duty if there was anyone else who was able to cut hair. The reply came that there was a young stoker who might be interested. I was asked whether I would be willing to take on the position to which I replied that I would be very happy to do so. This was to be the start of my hairdressing career, which would yield many happy memories as well as earning me as much money as I got from the Navy. It was essential that I had a day job so that my free time in early evenings could be spent hair cutting.

The "Barbers' Shop" in Hood was on the port side of the upper deck - one deck down. I remember that it certainly was a lovely room with a 6-foot wide mirror, water geyser and all the equipment that a budding barber needed. The other thing that struck me about the room was that it was a rather odd shape. This was due to the fact that one of the walls was curved. The wall was formed by the massive vertical steel cylinder or "barbette" which ran down through the ship and on top of which sat "B" turret. Apart from a barber's shop it also served me as accommodation as I used to sling my hammock up in the corner of the room to sleep. There was much more room in there than there was out on the mess decks.

I shared the barber's shop in "Hood" with a Marine Bandsman. We each charged 4 pence a time and paid 30 shillings to the Sports Club fund at the end of each month. The balance of the money I made was mine to keep so it was a good way of topping up your pay from the Navy. It also meant that you were not ashore spending your money all the time. I soon found that there was no shortage of customers.

When the officers had their haircut they would often say to me, "How much do I owe you?" and I would reply, "Well, you can buy me a bottle of beer if you like, Sir." I liked a bottle of beer as a change from the daily issue of rum that we had in the Navy back then. The ratings would often pay me in kind with their tot of rum. Sometimes, when I was busy in the shop, I would ask a stoker whether, for a bottle of beer, he would cover one of the shorter "dog watches" for me whilst I worked in the shop.

Another good thing about being the barber was that you were often the first to hear what was going on. I remember that whilst we were at Gibraltar in "Hood" during the spring cruise of 1923 I was cutting a Commander's hair when he said to his messenger, "Go and tell the Engine Room Commander that I want to speak to him." Being in the Engine Room myself I thought it might be worth while finding out what he had to say, so I made the cut last a bit longer than usual. When the Engine Room Commander arrived I heard them talking about the ship going through the Panama Canal and how much clearance there might be. "It's going to be tight to get her through. About 6 inches each side, I reckon," was the Engine Room Commander's view. That was the first time I heard mention of the Empire Cruise, which Hood was to set off on in November 1923.

Unfortunately, a while later I found out that the Marine Bandsman with whom I shared the shop was "playing dirty" with me. We each charged 4d for a cut and the money was supposed to go into a kitty to be shared out at the end of the week. Being the new boy I had accepted this arrangement in good faith. However, I started to think that my share seemed low for the number of cuts that I was doing and eventually realised what was happening. The Bandsman was often being given a sixpence by his customers, which he would put in his top pocket. He would then give them the 2d change out of the shared kitty, which I was filling with my own takings! This meant, of course, that of the 4d that I put in only 2d remained there for the payout at the end of the week. When that arrived and the money was halved between us I was ending up with only a penny a cut! One night when he went out I took the opportunity to confirm my suspicions and found several sixpence pieces in his top pocket. When he came back I confronted him and said that one or other of us had to go. I didn't tell him that I had found the evidence in his top pocket - his conscience would tell him that. It didn't come to either of us having to leave but the takings were a lot higher from then on although I never really trusted him again afterwards.

When I first joined "Hood" the Admiral flying his flag from her was "Titchy" Cowan. He was a terrible chap who never missed a chance of telling off any of the officers or ratings. I remember that he would often report the boat crew boys for not pulling properly. On one such occasion, he had a group of Boys sentenced to 5 days in the cells. Boys could not be given time in the cells so he had the whole group rated to Ordinary Seamen. I heard that this was subsequently over ruled and that they were rated to Boys again but it is a good example of what a hard man he was and how he would always find a way of exercising his will on the men under his command. When he needed to address the crew he had to stand on a box if anyone were to see him, as he was a very short man.

At Divisions on the first Sunday of the month he would stand on a spit-kid on the quarter deck, and the whole ship's company would march and salute him.

In May 1923, Rear Admiral Cowan left Hood and was replaced by Rear Admiral Field. Towards the end of the summer the rumours of our world cruise were confirmed. Rear Admiral Field was to be promoted to Vice-Admiral to lead what was to be officially known as the Cruise of the Special Service Squadron. The cruise would be a complete circumnavigation, calling in at various outposts of the Empire in order to "show the Flag" and encourage the nations of the Empire to combine their naval resources.

We left Devonport on 29th November 1923 by which time the Press had labelled the venture "The Empire Cruise" or "World Cruise", although some of the sailors called it "The World Booze!" We didn't get a big send off - it was a very low-key affair with just family members at the quayside. We would not see our homeland for another 11 months.

The Squadron comprised "Hood," as flagship, the Battle Cruiser H.M.S. Repulse and five light cruisers - H.M.Ss Delhi, Dauntless, Dragon, Danae, and Dunedin who joined us later at sea. In the early days of the cruise we passed the Canary Islands and continued on down the west coast of Africa to reach our first port of call - Sierra Leone. I remember to this day how very hot it was there. There was a film crew aboard and as soon as we landed they went ashore to photograph the locals and such sights as there were. Unfortunately, one of the seamen who went with them soon returned to the ship suffering from sunstroke and my services as ship's barber were required to shave his hair off so that ice bags could be applied to his head. When he recovered he was not at all happy about what I had done to his hair!

Something else that stands out in my memories of the early days of the cruise is the fascination we all had that, along with all our other equipment, we had brought along a Rolls Royce car complete with driver. This was needed for various ceremonial occasions but it must also have been an excellent way of showing off the best of British motorcars throughout the Empire.

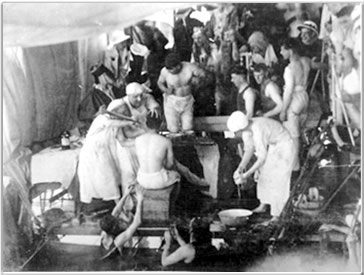

Members of King Neptune's Court shave a victim before

he is dragged down into the bath to be washed.

Leaving Sierra Leone, we continued to make our way down the west coast of Africa until we reached the equator - known to all seamen as "the line." Here we were hailed by “King Neptune” and his court. Most of the ship's company had not been south of the equator before so we lined up to be initiated into the "order of the bath" by being lathered-up and shaved with a wooden razor before being thrown into a huge bath which had been erected on the quarter-deck! No one was spared this ordeal as King Neptune treated Officers and men alike. After the ceremony we received our certificates to record that King Neptune had decreed that we could continue on our way.

Our next port of call was South Africa where we arrived on 22nd December. We were greeted by great storms, and winds known locally as the "south-easter," which made it very difficult to get boats ashore. Whilst in South Africa we visited Cape Town, Port Elizabeth, East London and Durban and had bad weather at all of these places, but were given wonderful receptions by the people.

On leaving South Africa we rounded the Cape and made our way up the East coast of Africa until we reached Zanzibar. What I remember most about there is the youngsters who used to come up to you and say something like "You very good man, master," to which came my reply, "What the hell do you want?" All they wanted though was to swap some of the local fruit for some of the food that we had on board ship. They came bearing great bunches of bananas and other fruits.

Having crossed the Indian Ocean, we came to Trincomalee, Ceylon. I had some leave and took the opportunity to take a trip up into the hills to have a look at the coffee plantations. I also visited Kandy, the capital of Ceylon, with a group of officers and men. Sadly, Stoker Petty Officer Wood, from H.M.S. Repulse, was killed when a bus overturned during this trip. His funeral and burial were later held in Kandy.

On we went to our next stop - Singapore. I suppose it must be the weather that sticks in one's mind most as I clearly recall it raining very hard whilst we were there. I went shopping and bought a tea set for £5. I still have the tea set today!

Our passage through the Indonesian Islands took us south and onwards to Freemantle in Western Australia where we moored alongside the wharf. We were overwhelmed by the thousands of visitors who had come to welcome us.

When we arrived at Adelaide, I again had a period of leave and met up with a man named John Cole who had been born at Ledstone - my own home village back in Devon! I had known John during my childhood days and had last seen him in 1908. He was now a butcher in Adelaide. I had written to him when the cruise became definite and had arranged to meet him. I also met up with another man named Heath who had also been in the village during those early years of the 20th century and who was now enjoying life in Australia as a sheepshearer.

Of course, the highlights of our time in Australia came with the open days. The public were allowed free entry to the ship and the freedom to roam wherever they liked. Officers and men remained aboard to act as guides. I recall that some of the younger chaps were very quick to pick out the best spoken and best dressed amongst our visitors in order to make sure that they got a healthy tip at the end of their guided tour.

Crowds disperse at the end of an Australian open day

I acted as a guide in the Engine Room and it was packed to capacity down there. On one occasion I showed two ladies around and spent some time explaining to them the circulation and condensing system. Only later did I discover that both were married to Engineer Officers so I had only explained to them what they undoubtedly already heard about on a regular basis from their husbands.

Next port of call was Hobart in Tasmania. Hobart was a lovely place but I will always remember it most of all for a small 'diplomatic incident' that happened whilst we were there. The Admiral had gone ashore and had given a speech in which he had said that the Navy today was mainly men drawn from prisons and borstals whereas in earlier times they had come from good homes. Of course, he had meant to say this the other way around, but soon the local papers were full of 'the Admiral's gaffe.' I gather that he had to make an apology. After that, whenever we went ashore at Hobart we had conversations with the locals along the lines of, "How long have you been in the Navy then?" "Oh, just over five years." "And how long have you still got to do?" "Oh, another seven."

To which came the reply "My goodness, what ever did you do - it must have been something quite serious!" It was all good-humoured leg pulling.

About the same time the "Hood jokes" started. We were getting used to being called "Cook's Tours." One joke that stands out in my mind is this one. "Why is the Empire Cruise like a Ford car?" Answer: "Because the Hood is the best part of it!"

Onwards to New Zealand where we arrived at Wellington on 24th April 1924 – the day before ANZAC day. A few days later hundreds of us were involved in a ceremonial march through the city, watched by thousands of people. After the march I met my Uncle, George Stone, and a cousin. As a lad I had spent the odd weekend in Plymouth with Uncle George who was a stonemason by trade. He and his son had emigrated to New Zealand in about 1920. They came back with me on board “Hood” and, the following day, I went to ask the Commander if I could have some leave to spend time with them. The Commander was not very happy at my short notice application and told me that I should have applied weeks ago but I did manage to get seven days' leave and spent it at their home. They took me all over the city. I also got to meet all my relatives over there: Uncle George and Aunt Polly and many cousins, one of whom, Ida, had married an Army tailor named John Adams who had also gone out to New Zealand from England.

Whilst in New Zealand the ship was visited by Admiral Jellicoe. We all knew Jellicoe well as the Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Fleet at Jutland during the War and afterwards a First Sea Lord. At the time of our visit he was the Governor of New Zealand. When we left Admiral Jellicoe travelled with us in “Hood” on to Auckland.

At Auckland, I was again allowed leave and took a trip by train up to the springs at Rotorua. Admiral Brand, who was in command of the Light Cruiser Squadron, came with the party. We discovered that the Maoris kiss by rubbing noses. The Maoris also told us that they used to have wars, "but we let the British do that for us now." We all laughed at that one. They also told us that Captain Cook's pig had fallen into the hot springs and that they had rescued everything bar the grunt!

Admiral Brand I remember from that trip as being a really nice man. Sadly whilst we were on the cruise, he received the news that his wife had died back home in England.

Leaving New Zealand behind, we sailed to Fiji and then on to Honolulu. I remember Honolulu for two things. Firstly, the very modern docks and secondly the fact that we couldn't get drinks because of prohibition.

The Squadron continued its journey across the Pacific and came eventually to Canada, calling first at Victoria and then at Vancouver. Whilst there we were told that a contingent of the crew were to travel by train through the Canadian Rockies to rejoin the ship at Halifax on the East Coast of Canada. My name was initially amongst those scheduled to take this passage but I said to the Chief that I didn't want to miss the Panama Canal. My request was granted and so it was that I ended up staying on the ship. When I look back now I wonder whether I made the right decision, as I would have loved to see the Rockies. Then again, I would not have wanted to miss the unique opportunity of being on the largest warship in the world as she passed through the Panama Canal.

As we made our way down the West Coast of the United States we parted company with the Light Cruisers. They would not be coming through the Panama Canal with us. Their route would take them down to the countries of South America before rounding Cape Horn.

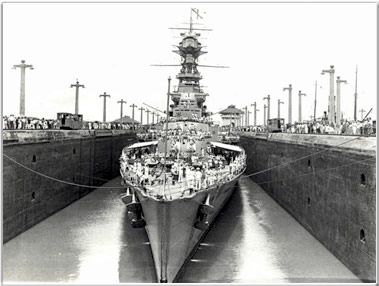

Hood is eased through one of the Panama Canal's locks

The passage of the Panama Canal was, to me, the highlight of the entire cruise. I was most fortunate in that the week that we made our passage through the canal I was scheduled for a motor boat course which was to take place on the ship's boat deck, so I was in an ideal position to see all that was going on.

The most spectacular part of all was when "Hood" passed through the canal's locks. As the Commander had suspected in the barber's shop at Gibraltar more than 12 months before, the clearance on either side was minimal. There were 4 small engines known as "mules" which ran on rails and were lashed to "Hood" with wires. The mules were there to ensure that "Hood" was kept straight and away from the sides of the lock as she eased her way through. As the lock filled it was incredible to think that water alone could lift "Hood's" 45, 000 tons with such ease.

Apart from the narrow locks, other sections of the canal were quite wide - like a broad river. I remember that we spent a day moored at Panama City and, whilst we were there, there was another torrential rainstorm.

Having completed our passage of the Panama Canal we headed north, calling in at Jamaica, Halifax, Quebec and Newfoundland before heading home across the North Atlantic.

We returned to Plymouth on 28th September 1924. This wonderful Cruise had taken us 11 months and a distance of over 38,000 miles, crossing the equator many times. It was the first occasion such a voyage had been undertaken by the modern Navy. (My family recently surprised me by obtaining from the Imperial War Museum a video copy of the official film made during the cruise – of course it is “silent” and in black and white.)

I found that my barbering had made me a considerable amount - £100, which was certainly a great deal in 1924.

For part of the time that I was in "Hood" I was on picket boat duty. This was something that I didn't like too much as it kept me away from my duties in the Barber's Shop. In the picket boat you would be on your own in the small Engine Room with just a Chief Petty Officer in over all charge so there was a lot of responsibility and you had to do everything yourself. We used to have regular unofficial races with our boat pitted against the other picket boats. When you got back to "Hood" the brass funnel that each picket boat had would be covered in salt from the spray and you would have to clean it so that it shone before your duty finished!

On returning from the Empire Cruise I was due to leave "Hood" but I really wanted to stay in the ship. I came up before the Commander who asked me "Why do you want to stay?" I had not planned my reply particularly effectively and just said something about having invested time and money in setting up the barbering in "Hood." This did not impress the Commander who pointed out that I had done over 6 years in the Atlantic Fleet and that I was now due for foreign service.

Not long afterwards I found out that even if I had managed to convince the Commander of my value to "Hood" it would have made little difference as the ship was transferred from Devonport to Portsmouth so I would have left her anyway.

By the time I left "Hood" I think I must have done every job in the ship that I was eligible to do as a stoker. There were a number of jobs right down deep in the ship - looking after the dynamos etc - that meant that you had to be in a room all on your own. I found the main difficulty in those jobs was to keep myself awake, as there was no one else to exchange a few words with. I often think of what it must have been like for those chaps down there when the ship was lost.

On leaving "Hood" I returned to barracks at Devonport. Whilst I was in barracks the "Empress of India" commissioned and I was placed on stand-by to be drafted to that ship at one point. However, that all came to nothing and I was told that my new ship was to be H.M.S. Chrysanthemum, which I was to join at Malta.

Chapter 6 - In the Med: H.M.S. Chrysanthemum

I served in H.M.S. Chrysanthemum, a sloop, which was, for most of my time in her, based in the Mediterranean at Malta from 1925 to 1927.

I remember that "Chrysanthemum" was the subject of some mess deck gossip and leg pulling at the time. About a month before I joined her she had been taking part in one of her usual duties, that of towing targets for larger ships - battleships and the like - to practise firing at. The targets, which were quite large, were towed about 50 yards behind "Chrysanthemum." On one occasion however, things had not gone to plan as the "Empress of India" - the ship that I had almost joined - had put a 6" shell through "Chrysanthemum's" stern. By the time I joined the "Chrysanthemum" the piece of metal with the shell hole through it had been replaced and was mounted on the quarterdeck as a sort of "battle honour". The thing I have always found hard to understand is that after this incident the "Empress of India" was awarded a cup for best gunnery!

Leading Stoker Stone (left) & Stoker Edwards

at Malta, 1926

One of the regular duties of "Chrysanthemum” was to put to sea at about 9pm on Sunday night. The Fleet usually put out for exercise on Monday morning and it was our job to provide advanced warning about the weather conditions. We were usually accompanied by the mail-boat that took the mail to Syracuse.

I had some good times in "Chrysanthemum" and I continued with my barbering. I was often sent for by other small ships to act as a travelling barber. I remember one day I ended up a bit drunk as the sailors were all paying me in kind with their tots of rum.

On another occasion when I was slightly inebriated whilst we were at Moudhros on the Greek island of Limnos, I came across a local man who was trying to push a donkey into the sea - presumably to wash it. I decided to lend him a hand but ended up pushing him into the sea as well as the donkey. At that point I decided to dive in myself. Up until then I had not been able to swim but afterwards I never again had any fears of going into the water. The next day, when they piped "Hands to bathe on the starboard side," I jumped over and swam. The Officer of the Watch said, "Look at that damn Rating - he couldn't swim yesterday!" In fact a couple of months later I found myself playing as goalkeeper in the water polo team.

We had a few nice trips around the coast of Italy and I recall anchoring at Naples from where, with some of my messmates, I was able to visit the ruins of Pompeii. We also visited Capri where I swam in the Blue Grotto and I remember the wonderful clear blue water.

I really enjoyed my two and a half years based in Malta. As it was a major naval base, there was plenty of entertainment – clubs, restaurants and bars. We would visit the Naval Club and I saw my first “talkie” at the cinema there – “All quiet on the Western Front.”

The ships would hold regattas, which I particularly enjoyed; and there was plenty of swimming.

I attended evening classes in English and Arithmetic as part of the preparation for promotion examinations and was promoted to Acting Leading Stoker just prior to leaving Malta.

About this time I met up with two of my brothers, Jack and Walter, whose ships were returning to England.

However, the main event that stands out in my mind from my two years in "Chrysanthemum" came in 1926 when we buried Lord Congrieve, the ex-Governor of Malta, at sea. After retirement he had lived at Gozo, the small island just off Malta, and had expressed a wish that, when his time came, he should be buried at sea. It fell to "Chrysanthemum" to perform that duty. Several prominent people from Malta attended the ceremony. The coffin was put in an iron case and lowered into the sea. Sometime afterwards we were detailed to take his widow to Marseilles as she was returning to England. It was a very rough trip and we landed her at Hyeres.

Chapter 7 - Back Home: P40 and Training at Devonport

On leaving "Chrysanthemum" at the end of 1927, I was drafted to "P40" which was a submarine chaser. "P40" was a very small but fast ship. I remember her as the only ship I served in from which I could dive off the upper deck. I was only in "P40" for about 9 months whilst I waited for a place on a course for Leading Stokers to advance to Petty Officer.

As I was based at Portland, I could go home to Kingsbridge for weekend leave. Since the train journey involved changing four or five times, I bought a little car – a Swift 8.9 horsepower, for £175 and after one lesson I drove it! I would frequently give fellow shipmates a lift and also other people en route.

I was notified that I had a place on the course, which was to be held in old ships moored adjacent to the barracks at Devonport and would last 3 months. During this course I learned my trade, which was boilermaker/bricklayer. It might seem odd to say that whilst in the Navy I was trained as a bricklayer but the boilers on ships were all lined with firebricks, which had to be replaced from time to time. We were shown how to crawl inside the boiler attached to a rope in case anything untoward happened. Once inside the boiler you had to chip out what remained of the damaged bricks and replace them with new ones.

I was notified that I had a place on the course, which was to be held in old ships moored adjacent to the barracks at Devonport and would last 3 months. During this course I learned my trade, which was boilermaker/bricklayer. It might seem odd to say that whilst in the Navy I was trained as a bricklayer but the boilers on ships were all lined with firebricks, which had to be replaced from time to time. We were shown how to crawl inside the boiler attached to a rope in case anything untoward happened. Once inside the boiler you had to chip out what remained of the damaged bricks and replace them with new ones.

At the end of the course there were various possible outcomes. Depending on how you had done you might be confirmed as a Leading Stoker or passed for Petty Officer or Mechanician candidate. If you were really bad you might even lose your Leading Stoker status. I was too old at the time to be put forward as a Mechanician candidate and was happy to be passed as Petty Officer.

Chapter 8 - Carrier Service: H.M.S Eagle

In 1929, following the Leading Stokers' course, I was drafted to the aircraft carrier H.M.S. Eagle, again based in Malta, where we initially went into dock and carried out a refit.

My own part in this work involved stripping the brickwork out of number one boiler, laying new bricks and lining them with fire clay. My Engineer Commander must have been pleased enough with my contribution as he remarked to me "Leading Stoker Stone, you will be able to build you own house when you leave the Navy!"

One day I received a call that was to test my bricklaying skills and as well as my ingenuity. The Captain of the ship had said that he wanted the tiles of the bathroom floor in his sea cabin replaced as the glazing had worn off them. The shipwrights had been asked if they could do it and had said "no" as they were all tradesmen and considered that it was a tiler's job. My Engineering Officer asked me if I might be able to do it as I had bricklaying skills that he thought I might be able to transfer to tiling. I said that I would have a go. The preparation was hard work as, when I had lifted the old tiles, I found an inch or so of special cement that needed to be removed. Then came the real problem - how was I going to cut the tiles? However, luck was on my side as, whilst I was ashore at Malta, I happened to meet a local man who knew how to cut tiles and, for a bottle of beer, he gave me a bit of instruction. Following this, I managed to lay the tiles well enough but was then faced with the problem of the grouting. The cement was brown and would not have looked very attractive as grout but I came up with the idea of mixing the cement with some of the white powder that we used throughout the ship to clean the brightwork. As I had hoped, this combination made a nice white grout. Finally, after I had finished the grouting, I covered the whole area with sawdust for a while which absorbed any excess moisture. One of the shipwrights got to see what I had done and asked me "Stoker Stone, where did you get that bloody grout?" "That's a secret," I replied. When the Captain saw it he was really pleased. So pleased in fact that he asked if I could do his main cabin as well. I did that as well but was not quite so pleased with the result - the tiles seemed a lot more difficult to lay perfectly straight in that room.

Later whilst I was in the "Eagle" came one of my "claims to fame" - I got to cut the hair of Major Raymond Franco - General Franco's brother. His seaplane had ditched in the sea after engine failure and had been lost for some days. "Eagle" found him and picked him up together with his three-man crew. Having hoisted plane and pilot on board, the Commander sent for me to cut our guest's hair. I remember that well because instead of paying me with one bottle of beer, as was the custom for the officers, he said, "Have two".

On "Eagle" the routine was different, which I liked. When aircraft were landing the Engine Room and Boiler Room crews were notified by the bridge. We were not allowed to adjust the sprayers, as there was a danger of making smoke, which would make things more difficult for the pilots. On the bows of "Eagle" there was a steam pipe by which the Captain was able to tell whether he had got the ship lined up correctly in relation to the wind.

William at Rio de Janeiro on the flight deck of H.M.S. Eagle with some local girls

One of the cruises on the "Eagle” stands out in my mind. We went across to South America and spent a few days anchored off Rio de Janeiro. A few of us took the opportunity of a day's leave to make the ascent of Sugar Loaf, which overlooks the City and Bay. We were about two thirds of the way up when I remarked to one of the Chiefs how small the ship looked from the height we were at. "Yes," replied the Engineer Commander, " and she'll look a lot smaller tomorrow when we've gone!"

Also during that trip we had the usual ship "open days" when the public were allowed aboard. Another sailor and I got chatting to a couple of local girls who said that they would return the favour of our guided tour of the "Eagle" by showing us around Buenos Aires and the surrounding district. So when we came ashore they were waiting with an open-top car and took us for a drive. Suddenly they stopped and said “Buenos Aires means good air and you sailors are smoking those beastly cigarettes!” So we threw them away. We went to their house – they were

lovely people - and they drove us back to our ship about 8 o’clock that evening. They said, “You will write to us, won’t you?” We said we would but needed their address and got them to write it on my Players packet. Of course, the next day I smoked the cigarettes and threw the packet away! I was sorry because they were really nice girls. I still have a photo of us on the flight deck.

One day we had an unexpected visitor when one of our own planes returned from Rio with a passenger on board. He turned out to be the Prince of Wales (later the Duke of Windsor). He had been forbidden by his father, King George V, to fly onto a ship but he had taken the chance. He was well entertained and, in fact, attended a dance held in the hanger by the ships officers and to which various local dignitaries also came.

We returned to Devonport in 1931 and I left H.M.S. Eagle as Acting Stoker Petty Officer.

Chapter 9 - Back to Small Ships

In August 1931, after a few weeks in barracks at Devonport, I joined the sloop, H.M.S. Harebell, a sister ship to H.M.S. Chrysanthemum and, like her, fuelled by coal. Our main duties were fishery protection. Although we were based at Portland, we visited, among other places, Reykjavik in Iceland, Buckie in Scotland and Fleetwood in Lancashire. During my time in H.M.S. Harebell I was confirmed as Stoker Petty Officer. I left the ship at the end of 1933 and returned to Devonport.

In January 1934, I was drafted to a destroyer – H.M.S. Thanet which was part of the Reserve Fleet. Our duties were mainly to go to Belfast once a month to refuel other ships in the Fleet. Sometimes I would make this journey in H.M.S. Tenedos. This was an uneventful draft, although I do remember very rough crossings.

Around this time I was seeing Lily Hoskin. Lily was to be my wife but it could all have turned out very differently. I had known Lily since I had been a young man as she lived not far from us and was friendly with my sisters. Lily's father was the local churchwarden and I often used to go around to their house and cut the Church grass and spend some time with Lily in the evenings. Lily's mother was Scottish. One evening she must have thought that I was staying later than she would have liked because she put on a gramophone record "Good night, Good night…”!

On one occasion, not long before I joined HMS Carlisle in 1934, I had arranged to go with Lily to Plymouth but I didn't turn up. She wrote to me and said that I would have to decide whether I wanted her or my drinking mates. I didn't answer the letter and soon afterwards found myself drafted to H.M.S. Carlisle and heading off to the South Africa station. For the whole time that I was there we lost contact with one another. Lily moved to London and worked for two ladies, the Poultney sisters, whose brother held the office of Black Rod in the Houses of Parliament.

In 1937 I returned to Devon from South Africa and met up with Lily again, who by that time had also returned to Devon as her father had been taken ill. We were married the following year.

Chapter 10 - Foreign Service: the South Africa Station

Going back to 1934 I was drafted to H.M.S. Carlisle, to serve on the South Africa station at Simonstown.

The two and a half years I spent there were some of the best and happiest times of my life. The weather was good and my shipmates and I made many friends with the local people who had emigrated there from England. They often took us to places of interest and would regularly entertain us at their homes. On one occasion we visited a gold mine in Johannesburg – the deepest in the world.

A trip I particularly remember was one organised for a group from our ship to visit Kruger National Park. We were taken by car, stayed two nights, and saw all kinds of wild animals at close quarters.

I recall going to the races with my shipmates, and backing the winner!

At Durban a group of us had the opportunity of a free flight in a troop carrier plane. This was the first time I had been airborne and thoroughly enjoyed it.

Whilst out there I had the unusual distinction for a Stoker Petty Officer of being Captain of a gun crew. The station had four Howitzer guns, which were used in displays that we gave. Three of the guns were crewed by the seamen and one by stokers. The latter was formerly captained by a Seaman Petty Officer but he was Court Martialled after a misfire. The Chief was asked if he could suggest a replacement and he suggested me. One of the occasions that stands out in my mind was when the guns' crews went on tour to give displays. We travelled from Cape Town to Johannesburg for the Exhibition and went to Durban and East London as well. We doubled around the Exhibition fields, six stokers manning our gun, towing the guns with ropes. Later, dressed in old style sailors uniforms, we would all sing sea shanties.

Whilst I was on the South Africa station the Commander in Chief was Admiral Evans of the Broke. He was another whose hair I can claim to have cut. I used to go up to his house to cut his hair and remember him as another senior officer who appeared to me to be a very pleasant man. Admiral Evans had been one of the most famous men in the country during the early 1920s. Before the First World War he had been second in command of Scott's final Antarctic Expedition and he would give us lectures on his experiences there. Towards the end of the War he had made his name by his command of H.M.S. Broke during a famous destroyer engagement in the English Channel. Coincidentally, he had also once been Commander of H.M.S. Carlisle - during the early 1930s whilst she was on the China Station.

Another of my duties was to drive the Admiral’s Barge.

During 1936 it fell to "Carlisle" to make the trip into the mid-Atlantic to supply the smallest Island in the British Empire - Tristan de Cuhna. The thing that stands out most from this trip is the fact that we took with us a live bull! Apparently, a need had been identified to introduce some variety into the Island's bloodstock - hence the bull. The animal was hoisted aboard and accommodated in a wooden pen, which had been specially made between "Carlisle's" two funnels. An able seaman was assigned to feed and generally look after it. Of course this led to the usual seaman's banter and leg pulling which this seaman had to fend off. "I see we've really got some bullshit on board this time!" is one comment that stands out. I can't remember if our "bull handler" offered a reply. There were other animals too - chickens certainly, plus the usual more conventional supplies.

When we arrived at the Island we had a few days free whilst the stores were off loaded. The Islanders had no money – they just bartered. I remember that the fishing there was exceptionally easy and that the fish were enormous. Also, the seaweed was so dense that when the anchor was weighed two Shipwrights were needed to cut weed off with an adze.

During our frequent exercises at sea, we would regularly visit ports along the east coast from Simonstown - Port Elizabeth, East London, Dunbar, and Lourenco Marques.

Whilst at Simonstown, we were often called out to help extinguish fires on the slopes of Table Mountain.

In early 1937 we left Simonstown waved off by a huge crowd of people, including the friends who had been so good to us. On arrival at Plymouth, we were greeted by another crowd including my sister Mabel and her husband Tom Rundle.

Following leave, I returned to barracks at Devonport and was subsequently rated to Chief Stoker.

Chapter 11- H.M.S. Salamander

In September 1937, I was drafted to the Minesweeper H.M.S. Salamander, stationed at Portland, Dorset. She was the ship in which I would see my early wartime service.

Chief Stoker Stone on leave at Goveton, 1937

On 27th May 1938, I married Lily Hoskin at Buckland-Tout-Saints, Goveton, near Kingsbridge.

By this time "Salamander" had sailed to Devonport for refitting and I was stationed in the barracks. Following our wedding, Lily and I lived in a flat at Plymouth, but when "Salamander" returned to Portland we rented a flat there where we lived for some months. I was often out minesweeping but was able to return to our home when the ship docked.

Lily became pregnant, but a week before our baby was born the ship left for Sheerness and never returned to Portland! I remember that time well - the air was filled with barrage balloons as defence against air attacks.

Our daughter Anne was born at Portland on the 28th August 1939 - just a week before war was declared! Not until the baby was three weeks old was I able to get special permission for long-weekend leave. Eventually Lily and Anne left Portland and returned to stay with Lily's parents, who had now retired to Wrangaton, near Plymouth.

Early in the War I lost one of my nephews, Leslie Edgecombe. Just a fortnight after the outbreak of war he had been lucky to survive loss of the aircraft carrier "Courageous" which was sunk in an attack by the German submarine U29 on 17th September 1939.

He had told me that, on that occasion, as he was trying to get out, he had heard one of the Petty Officers shouting, "Follow me!" Although he could not see the Petty Officer, he had followed the sound of his voice and managed to get out and had been rescued. Although my nephew was saved many of my friends were lost with the "Courageous." However, my nephew was not so lucky a few months later when, on 8th June 1940, "Courageous's" sister ship "Glorious" was lost off Norway in action with the German Battle Cruisers "Scharnhorst" and "Gneisenau" following the evacuation of Norway.In those early months of the war "Salamander" was stationed at Grimsby and we were responsible for coastal minesweeping operations around the northeast. I managed to rent rooms at Cleethorpes and Lily and Anne travelled all the way up from Devon, by train, so that we could be together. On one occasion the ship had a close call. I was one deck down at the time but I gather that a mine got caught around one of the sweeps as it was being winched back in. Fortunately, someone spotted it and gave the alarm. They managed to free the mine from the sweep but in doing so, or shortly after, it detonated and blasted the side of the ship. Although there was no damage that threatened the ship itself, one of the plates, which separated the oil tanks, was ruptured and we had to go into docks to have that repaired.

In May 1940, when Germany advanced through Belgium and France, we were ordered by the Admiralty to the south coast to help with the Dunkirk evacuations. We did five trips to Dunkirk in all, rescuing 200 to 300 men each time. Things got worse each trip we made. Our final trip was on 1st June by which stage there was the wreckage of sunken ships all around and burning oil tanks by the dockside. Lines of troops were all marching towards the sea. We were anchored off the beach with one of our sister ships, the 'Skipjack', only about fifty yards away. At about 8am the German dive bombers came over and attacked 'Skipjack.' One of the attacking planes was shot down but 'Skipjack' was badly hit and capsized. She must have had about 200 men on board. I had to say "God, help us." I believe to this day that He did.

During our trips to Dunkirk, I was often stationed on the quarterdeck helping men get aboard "Salamander" as they swam out from the beach. Other groups of men had managed to find boats and row out to the ship. On one occasion I had a rope around a badly injured soldier who had bones sticking out of his trousers. Just as I tried to pull him in, the ship went ahead and I lost him. I don't know what happened to him.

Unknown to me, on our way back on the final trip, we were attacked by a submarine that fired a torpedo at us. When we got back to Dover the Coxswain and the Able Seaman on the wheel said to me "Chief, we held our ears today and waited for the explosion. Jerry fired this torpedo that was coming straight for us amidships." "Salamander" had been saved by her shallow draft - the torpedo had passed straight underneath us. The only explanation that we could think of to explain our lucky escape was that the German submarine had mistaken us for a destroyer and had set the torpedo to run at a greater depth than the "Salamander's" draft.

Those were awful days but one just carried on as if nothing had happened - there was nothing else that you could do.

In all the years since Dunkirk I had never come across anyone whom we had rescued in the "Salamander" until the summer of 1999. It was then that, whilst at a reunion of the Henley Branch of the Dunkirk Veterans Association, a chap came up to me and said, "What ship were you in at Dunkirk, Chief?" "Salamander," I replied. "You saved my life," he said. He told me that he had broken into a boat shed at De Panne in Belgium with some other soldiers and pinched a rowing boat. They had started to row home when we picked them up. It is pretty unlikely that they would have made it all the way back across the Channel in the rowing boat.

Following Dunkirk "Salamander" was put in to the Royal Albert docks in London to undergo repair to the damage that had been sustained during the evacuation.

Lily and baby Anne again came up from Devon to stay with friends at Wyndham Street, near Marble Arch, and I was able to spend the nights there.

After repairs we sailed to Invergordon in northeast Scotland, where we were based whilst on duty escorting convoys.

Later the ship was transferred to Aberdeen for modifications to the minesweeping gear. Lily and Anne were again able to join me and we all stayed locally for a short while.

Soon afterwards came the devastating news of the loss of the "Hood." I remember well the day I heard that she had been lost. I was on leave with my family at Wrangaton at the time. I just couldn't believe it, and was unable to eat my lunch.

Those were dark days and the only ones in the war that I really felt down. A month or so later Hitler attacked Russia, which brought that country into the war. I felt that Russia coming in on our side was one of the best pieces of news I had heard in a long time. I had no real doubt about the outcome after that.

Of course one of the results of Russia becoming our ally was the start of the Russian convoys. H.M.S. Salamander was one of the ships which formed the escort on the very first such convoy, code named Operation "Dervish". The merchant ships left Liverpool on 12th August 1941 and formed up at Iceland on 20th August where they were joined by "Salamander" and the other escort ships. We provided escort for the passage to Arkhangel, where we arrived on 31st August. Unlike many of the later PQ convoys, "Dervish" proved to be an uneventful trip for us. As a Chief Stoker I was in charge of all the other junior Stokers on the ship.

Something that I do remember well from that trip is that “Salamander” was refuelled at sea. As I recall we took on about 50 tons of fuel oil. Being in charge of everything to do with oil and water in the ship, I was responsible for the "Salamander" end of the refuelling operation. All went smoothly from above decks.

During our return from Russia the Engineer Officer told me that when we arrived back I was due to leave the "Salamander". I asked to see the Commander, as I didn't want to leave. The Commander would not change his mind though and said that I had been on the ship for 4 years and was due for a move. As it transpired he did me a favour as, later in the war, "Salamander" was nearly destroyed. She was minesweeping off Le Havre on 27th August 1944, when she was mistaken for an enemy vessel by some RAF Typhoons. During that action our own aircraft sank two minesweepers, the "Britomart" and the "Hussar" and badly damaged "Salamander" - blowing off most of her stern.

So it was off to barracks for me to await a new draft. I had not been there a fortnight when I received a chit to say that I was going to be drafted. That day another Chief whom I knew greeted me "Morning Chief," he said, "Morning be buggered," I replied. "What's the matter with you old so and so?" he said. "I've got a draft chit," I said. "I know you have," he said "I'm going with you! We're going to Wallsend to stand by a new ship." "Oh, that's a lovely job!" I said.

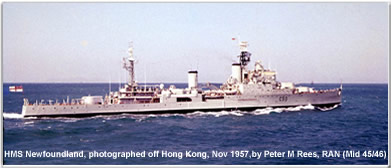

Chapter 12 - H.M.S. Newfoundland

In December 1941 I arrived at Wallsend, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, as part of the advance party on a new ship, the cruiser H.M.S. Newfoundland which was still under construction. As I was to be here for some time, I was able to rent a house so that Lily and Anne could join me.

At first I was a bit concerned about "Newfoundland" as, being a new ship, she would be fitted out with a lot of modern electrical equipment whereas I was used to older ships with reciprocating equipment. But the ship gradually grew up around me so that, by the time she commissioned at the end of 1942, I knew every inch of her. I used to spend some of my spare time copying plans of the ship and have drawn her from stem to stern.

In early 1943 we did working up exercises at Scapa Flow, before sailing to Devonport. I was horrified to see the utter devastation of Plymouth as a result of the German bombing. Whilst based there we were on Atlantic convoy duty, but by the spring we were in the Mediterranean, getting ready to support the invasion of Sicily.

I remember that we went to Bone in North Africa to oil. Much of that area had been destroyed by the Germans as they evacuated. One night whilst we were there "Newfoundland" was under attack from enemy aircraft and the Chief Engine Room Artificer "Geordie" Pearson, and I were at our Action Stations. He was extremely jittery, and not surprisingly, since he had been in H.M.S. "Edinburgh" when she had been sunk. He was picked up by a Russian destroyer and that was sunk too!

Before the main invasion of Sicily there were a few small Islands that we had to capture. One of these was Lampedusa. "Newfoundland," together with several other cruisers and destroyers, carried out a heavy bombardment of the island on 8th June 1943 as an overture to the landings. One thing in particular stands out in my mind from that operation. Following the bombardment we trained our binoculars on the coast and could see on the beach one of the local women standing and waving a white flag. The Yanks named her "Lampedusa Flossy".

When the time came for the main invasion of Sicily, Operation "Husky", "Newfoundland" was again sent to provide shore bombardment in support of the landings. Usually, we spent 3 days off the coast of Sicily and then went back to Malta to refuel and provision the ship.

Later on we had a Regatta at Malta and I was on the crew of a whaler. Our boat’s crew was all Chief Petty Officers - the oldest men in the ship - so we didn't expect to win much but, to our surprise, we won four out of the five races. Afterwards General Montgomery, who happened to be in Malta at the time, came aboard the ship and said to us, "You men are fighting fit. The oldest men in the ship and you win four races out of five!"

My job at the time was "D.B. Chief". That put me in charge of the ship's "double bottom" where the oil fuel was stored. I had to monitor the rate that the fuel was being used at and ensure that is was drawn evenly from the many fuel tanks.

"Newfoundland" was part of the 15th Cruiser Squadron, which itself was part of "Force K" under the Command of Rear Admiral Harcourt, who flew his flag from the "Newfoundland."

On 9th July we sailed from Malta and rendezvoused with some of the landing craft. During Operation "Husky" D-Day, 10th July, 1943, "Newfoundland," together with "Orion," "Mauritius," and "Uganda" the three other Cruisers in the 15th Squadron, provided support to the advancing troops by keeping up a shore bombardment. "Newfoundland" is recorded as having provided bombardment support on four separate occasions during that day.

During the next couple of weeks this support of the landings continued. Then, just after mid-day on 23rd July, "Newfoundland" sailed from Augusta heading for Malta. The ship had got up to a speed of 25 knots when, at 13:38 she was hit on the port side by a torpedo. I remember that there was quite a bit of damage to the ship - the rudders were blown off together with 6 bulkheads at the stern. Sadly, one man working on the quarterdeck was killed.

As "Newfoundland" limped towards Malta, a search for the submarine was immediately started by H.M.S Laforey and the other ships of the 8th Destroyer Flotilla. This chase was soon to prove successful. At 15:41 "Laforey" was herself subjected to a torpedo attack but the tables were soon turned. "Laforey" and "Eclipse" managed to force the Italian submarine, "Ascianghi," to the surface where she was sunk by gunfire at 16:23.

When we arrived at Malta "Newfoundland" was patched up. We were told more permanent repairs would be done elsewhere, which we all thought meant back in England. However, as we left the Mediterranean, we were told that we were on our way to Boston in the United States!

A while after this came the news that I had been recommended for a Mention in Dispatches for my work in "Newfoundland" during the "Husky" Operations. My award was eventually gazetted in the London Gazette on 30th December 1943 and I received a bronze oak leaf emblem to pin to the ribbon of my Campaign medal.

I shall never forget the journey across the Atlantic to Boston. The "Newfoundland" was still without rudders and we had to steer her by means of adjusting the speed to the port and starboard screws, which made life in the Engine Room hectic. Bear in mind too that we still had to zigzag the ship in order to avoid interception by submarines. At one stage some of the seamen rigged up a "sail" on the fo'c'sle out of the quarterdeck awnings to assist our steerage!

We spent about 8 months in Boston whilst "Newfoundland" was being repaired. When we got there the majority of the ship’s company returned to England. Those of us who remained were offered hospitality by local people, many of who had emigrated to America years ago. In my case, I was invited by a Mr and Mrs Pounder to visit their home in New Bedford, which was about 60 miles from Boston. Annie and her husband Bill, who was a carpenter by trade, originally came from Burnley in Lancashire. I went there nearly every weekend during the refit. They would never take anything for my keep but I did manage to get them a few bottles of whisky, which they found very acceptable!

I was in Boston for Christmas of 1943. It was so nice to be away from the war for those few months. Bill and Annie used to take me to the local Music Hall at the weekend and I would often end up on the stage dancing away or sometimes singing "All the Nice Girls Love A Sailor.” Once I had a week’s leave and they took me by car to New York where we visited the Empire State Building and many other places of interest. They were lovely people!

After the war, when I lived in Paignton, Bill and Annie Pounder came over to England on holiday to visit relatives. I was able to book them into a local hotel for two weeks and pay for them to stay there as a thank-you for all that they had done for me.

Eventually the repairs were completed and time came for us to leave Boston and head back home across the Atlantic. Our journey to England was completely unescorted. First we called in at St. Johns, the capital of Newfoundland to oil. Some of the chaps got a ‘run ashore’ but, being responsible for oiling the ship, I missed out on that one. When I went out on deck the dockyard mateys would shout across to me, one said, "Take good care of that ship Chief - I paid half a crown towards her!"

However, this was a great occasion for the people of Newfoundland. The ship had been partly financed by them, as Newfoundland was one of the colonies of the British Empire. There were great celebrations, civic ceremonies, a march through the city etc., and crowds of locals came to visit the ship. After four days there we finally sailed back home.

Afterwards I heard that we had lost radio contact with the Admiralty during the latter part of the journey and it had been feared that the ship had been lost, but we arrived safely in Greenock, on the River Clyde, although with very little fuel left in our tanks. This was shortly before D-Day, June 1944.

I travelled to Devon for leave by train, taking with me all the presents I had purchased for the family whilst I was in America. On my return to Greenock, Lily and Anne came with me and we rented a flat there for a few months during which time H.M.S. Newfoundland was being refitted. We would regularly see the liners ‘Queen Elizabeth’ and ‘Queen Mary’ in the Clyde as, during the war, they were used as troop carriers.

In September 1944 I left “Newfoundland” and rejoined the barracks at Devonport where I was based until the end of the war in Europe.

In May 1945, wearing khaki uniform with naval cap, I was drafted to form part of a naval party that would guard the Island of Sylt, off the extreme north-west German coast. Having had little previous experience of firearms, I got a weeks' training with revolvers before I was sent off.

We went across the channel and landed at Ostend. From there we were transported across north Germany in Army trucks. The towns in that area had been completely flattened on both sides by the allied bombing. I remembered some of my runs ashore at Plymouth, which had seen similar devastation and was glad to see it was not only the British cities that had suffered.